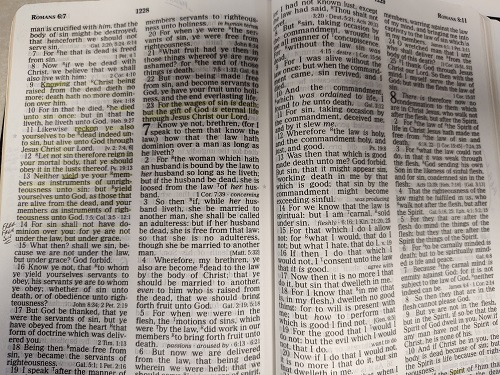

414 years ago today, the King James Bible was published for the first time in London, England. It was translated from the Majority Text (or Received Text), which was the text used by Bible believers for thousands of years.

The King James Version of 1611, also known as the Authorized Version of the Bible, “has been proven throughout history to be the greatest of all English translations.” The beautiful English prose contained in the King James Bible has had supreme influence in society, and is widely considered to be the greatest literary masterpiece known to man.

When King James the Sixth of Scotland succeeded Queen Elizabeth the First of England after her death, many different translations of the Bible were in existence, including the Bishop’s Bible, the Great Bible, and the Geneva Bible. To settle various religious grievances, King James called the Hampton Court Conference in January of 1604. During the Conference, Dr. John Reynolds, a Puritan leader and Oxford scholar, “moved his Majesty, that there might be a new translation of the Bible, because those which were allowed in the reigns of Henry the Eighth and Edward the Sixth were corrupt and not answerable to the truth of the Original.” King James then replied, “I wish some special pains were taken for an uniform translation, which should be done by the best learned men in both Universities, then reviewed by the Bishops, presented to the Privy Council, lastly ratified by the Royal authority, to be read in the whole Church, and none other.”

The king commissioned a new English translation to be made by 54 revisers representing the Puritans and Traditionalists. Due to death and other circumstances, 47 scholars and theologians wound up working on it. They took into consideration: the Tyndale New Testament, the Matthews Bible, the Great Bible and the Geneva Bible. The great revision of the Bible had begun.

From 1605 to 1606 the scholars engaged in private research. From 1607 to 1609 the work was assembled. In 1610 the work went to press, and in 1611 the first of the huge (16 inch tall) pulpit folios known today as “The 1611 King James Bible” came off the printing press.

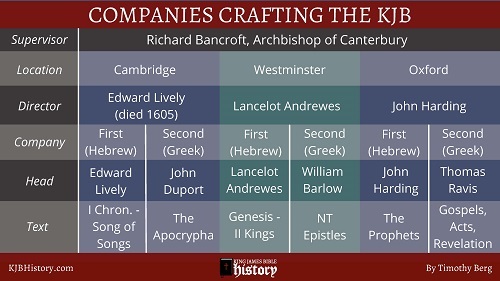

The process was a thorough one. These 47 men were organized into six Companies, two Companies at Cambridge, two Companies at Oxford and two Companies at Westminster. Each Company was given a portion of the scripture to translate. (Westminster was given Genesis – II Kings and Romans – Jude. Oxford was given Isaiah – Malachi, Matthew – Acts, and Revelation. Cambridge was given I Chronicles – Song of Solomon and the Apocrypha.)

Richard Bancroft came up with a set of rules that the translators were to follow. The process was guided by these rules. Rule #8 stated:

Every particular Man of each Company, to take the same Chapter or Chapters, and having translated or amended them severally by himself, where he thinketh good, all to meet together, confer what they have done, and agree for their Parts what shall stand.

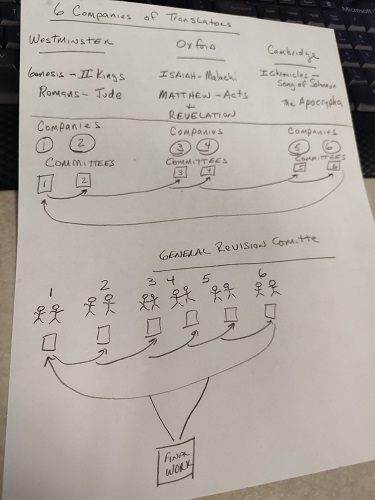

First, each one of the men from the company took a certain part. Then, privately, each individual member would go home and study and develop a proposed translation. Then they would get together as a Company and would review each copy. I’d give you my copy, and you’d give me yours, and we’d review and compare them until that Company of men came to the conclusion that “here is what we want to do.“

Bancroft’s Rule #9:

If any one Company hath dispatched any one book in this Manner [in other words, when they get through], they shall send it to the rest, to be considered seriously and judiciously, for His Majesty is very careful in this Point.

Next, each of the Companies (two at Oxford, two at Cambridge and two at Westminster) would all go home and study. They would take the portion assigned to them and study it. Each man would take all these different versions, the Greek and the Hebrew, and then they would come together. For example, each man would say, “Here’s what I think Romans through Jude ought to look like.” Then they would all come together as a committee and compare what each one has done individually. In doing that they arrived at what the committee thought the translation ought to look like.

When these people finished with their section, they sent it to every other committee. Each of the committees reviewed what each of the other committees have done.

There are revisions, revisions, revisions, reviews, reviews, reviews. Everybody works independently and then everybody gets together, and they work together and hash out their differences. It is checked and checked again. The work isn’t done by just one or two guys. You’ve got a bunch of guys sitting there working – one looks at it, another looks at it, everybody looks at it until they feel they have it right.

Bancroft Rule #10:

If any Company, upon Review of the Book so sent, doubt or differ upon any Place, to send them Word thereof; note the Place and withal send the Reasons, to which if they Consent not, the Difference, then to be compounded at a General Meeting, which is to be of the chief Persons of each Company, at the end of the work.

The process is still not finished. Finally, from each company/committee two men were selected to represent their group. Two men from all 6 companies (12 men total) and form a General Revision Committee.

Basically what they are saying is, “Before we get through, we’re going to have one big meeting. Two men from each of these committees are going to bring their committee’s work to this General Revision Board. That General Revision Board is going to review and issue the final version.

In early 1610, the twelve-member critical Board of Review met at Stationer’s Hall in London. The work of this Committee of twelve men was the only time that anybody in this whole process ever got paid anything. None of these other men got paid for what they were doing. They only had the privilege of being involved in a tremendous undertaking. The men on the Revision Committee were paid for their work by those that published the translation.

Here is a poor drawing of the process:

The entire process was done openly and not in secret, as some want to say. The public even had a chance to be a part of the process if they were qualified. According to Bancroft’s rules:

Rule #11

When any Place of Special Obscurity is doubted of, Letters are to be directed, by Authority, to send to any Learned Man in the Land for his Judgment of such a Place.

In other words, when they had something they were arguing about, and they couldn’t figure it out, but there was somebody over on the other side of the country who might have the answer, they were to go ask that guy to give them the answer and get his input. What Rule Number 11 did was to provide that specific help was to be sought for. “If you guys have an argument about a difficult passage, you should go find out if anybody who is not on the Committee knows.” This thing is not a closed group. Anybody in England can help, and you guys are supposed to go out and get them.

Rule #12 states:

Letters are to be sent from every Bishop to the rest of his Clergy, admonishing them to this Translation in hand; and to move and charge as many as being skillful in the Tongues; and having taken Pains in that kind to send this particular Observation to the Company, either at Westminster, Cambridge or Oxford.

If you knew something about these things, you weren’t supposed to keep it to yourself. The King put out a proclamation to be read in all the churches. He sent a letter to every preacher in England, and he saidbasically, “If you have anybody in your church who’s a good Bible translator, send him our way if he’s got some information and send it down here! “ In essence, the whole country was getting involved.

Published in 1611, the King James Bible spread quickly throughout Europe. Because of the wealth of resources devoted to the project, it was the most faithful and scholarly translation to date—not to mention the most accessible.

“Printing had already been invented, and made copies relatively cheap compared to hand-done copies,” says Carol Meyers, a professor of religious studies at Duke University. “The translation into English, the language of the land, made it accessible to all those people who could read English, and who could afford a printed Bible.”

Whereas before, the Bible had been the sole property of the Church, now more and more people could read it themselves. Not only that, but the language they read in the King James Bible was English, unlike anything they had read before. 400+ years later, and it is still in the hands of believers.

Sources: Textus Receptus Bibles (website), Britannica (website), Grace School of the Bible (Personal notes)