Dave at A Sound Day just wrapped up his monthly feature Turntable Talk. It was an interesting topic this time around and there were a lot of surprises as to who everyone chose to write about. This was my entry to the feature, which originally posted on Dave’s site on Monday:

It is time once again for Dave’s feature Turntable Talk. Dave features this every month on his site A Sound Day. This is the 39th edition, and he continues to come up with fantastic topics. This month is a fun one: Bands? We Don’t Need No Stinkin’ Bands! Dave’s instructions were simple: This time around, we’re looking for artists who left popular bands to go solo and did well (either commercially or else in your own critical assessment.)

I am sure that I did exactly what the other participants did when the topic was presented – I Googled. I was actually surprised at just how many artists moved from a group to become a solo artist. Off the top of my head I can list Diana Ross, Sting, Lionel Richie, Eric Clapton, Gwen Stefani, Ricky Martin, Peter Gabriel, Rob Thomas, Steve Perry, Lou Gramm, and Justin Timberlake. There are SO many.

In all honesty, I had my choice almost immediately. However, as I began to write about him, there was another artist connected with him that became more interesting to me. It was an artist who had solo success for a short time, and then a sad ending.

If I mention The Drifters I am sure you can name a few of their big hits. Under The Boardwalk, This Magic Moment, and Up On The Roof are just some of them. The Drifters were formed by my choice artist in 1953. His name was Clyde McPhatter. Let’s go back a couple years to see how it all came together.

Like many artists, Clyde McPhatter began singing in the church choir at his father’s church. In 1950, he was working at a grocery store. He entered the Amateur Night contest at Harlem’s Apollo Theater – and won! Afterward, he went back to working in the store.

One Sunday, Billy Ward of Billy Ward and the Dominoes heard Clyde singing in the choir of Holiness Baptist Church of New York City. He was immediately recruited to join the group. Clyde was there for the recording of their hit “Sixty Minute Man,” which was a number one song on the R&B chart for 14 weeks in 1951.

My original pick for this round was Jackie Wilson. Jackie was hired by Billy Ward in 1953 to join The Dominoes. That same year, Clyde left the group. He coached Wilson while they were out touring together. Wilson would leave in 1957. Apparently, Ward was not pleasant to work with. Wilson said, “Billy Ward was not an easy man to work for. He played piano and organ, could arrange, and he was a fine director and coach. He knew what he wanted, and you had to give it to him. And he was a strict disciplinarian. You better believe it! You paid a fine if you stepped out of line.”

Atlantic Records saw a Dominoes show and noticed that Clyde was not with the group, so they searched for him, found him and wanted to sign him to a record deal. Clyde agreed to sign on one condition – they allow him to form his own group. That group was the Drifters. While known as Clyde McPhatter and the Drifters, they released songs like Money Honey.

Elvis Presley covered Money Honey in 1956. In researching for this piece I was surprised to find that McPhatter and the Drifters did the original of another Elvis hit – Such a Night.

In late 1954, McPhatter was inducted into the U.S. Army. He assigned to Special Services in the continental United States. This allowed him to continue recording. After his tour of duty, he left the Drifters and launched a solo career. The Drifters continued as a successful group, but with many changes in personnel, and the group assembled by McPhatter was long gone by the time their greatest successes were released after he left the group.

It would take two years, but Clyde would finally get his first solo #1 R&B hit when he released “Treasure of Love” in 1956. It would top out at #16 on the US Pop Chart. I love his vocal on this one.

His biggest solo hit would come in 1958 when he recorded and released a song written by Brook Benton. A Lover’s Question would reach #6 on the Pop Chart. If I had to pick my favorite Clyde song, it would be this one. There is so much to love about this song. That acapella bass line being sung throughout the song is very catchy.

McPhatter would leave Atlantic Records and bounce from label to label recording many songs, but not having much success. His last top ten record would come in 1962 with a song written by Billy Swan. Lover Please was first recorded by the Rhythm Steppers in 1960. It was the title track from Clyde’s 1962 album of the same name. It would reach #7 on the Pop Chart.

Clyde did manage to have a top 30 hit in 1964 with “Crying Won’t Help You Now,” but when it fell of the chart, he turned to alcohol for comfort. He would record every so often, but nothing ever really did well on the charts. He always had a decent following in the UK, so in 1968 he moved to England.

He wouldn’t return to the US until 1970. Outside of performing on a few Rock and Roll Revival shows, he lived a very private and reclusive life. In 1972, Decca Records signed him and they were planning a a big comeback. That never materialized as Clyde passed away on June 13, 1972 of complications from liver, heart and kidney disease. This was brought on by his alcohol abuse years earlier. He was only 39 years old.

His legacy consists of over 22 years of recording history. Clyde was the first artist to be inducted twice into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, first as a solo artist and later as a member of the Drifters.

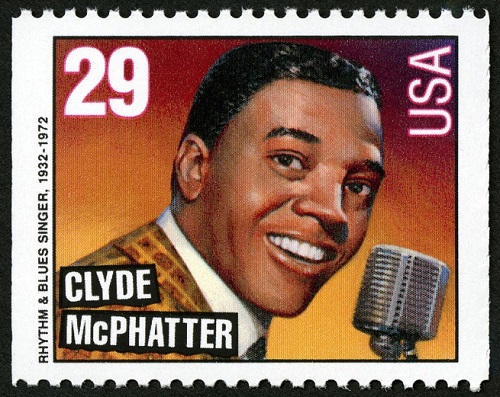

In 1993, Clyde was honored with his own stamp by the US Postal Service.

His career had ups and downs, and his hit songs were an important part of Rock and Roll history. Vocalists like Marv Johnson, Smokey Robinson and Ben E. King are all said to have patterned their vocal styles on Clyde’s. Others have cited him as a major influence as well. In the book “The Drifters” by Bill Millar, he says:

“McPhatter took hold of the Ink Spots’ simple major chord harmonies, drenched them in call-and-response patterns, and sang as if he were back in church. In doing so, he created a revolutionary musical style from which—thankfully—popular music will never recover.”

Thanks again to Dave for hosting another great round of Turntable Talk. I cannot wait to see who the other writers have picked and look forward to Round #40 next month.

Thanks for reading and thanks for listening!